|

|

|

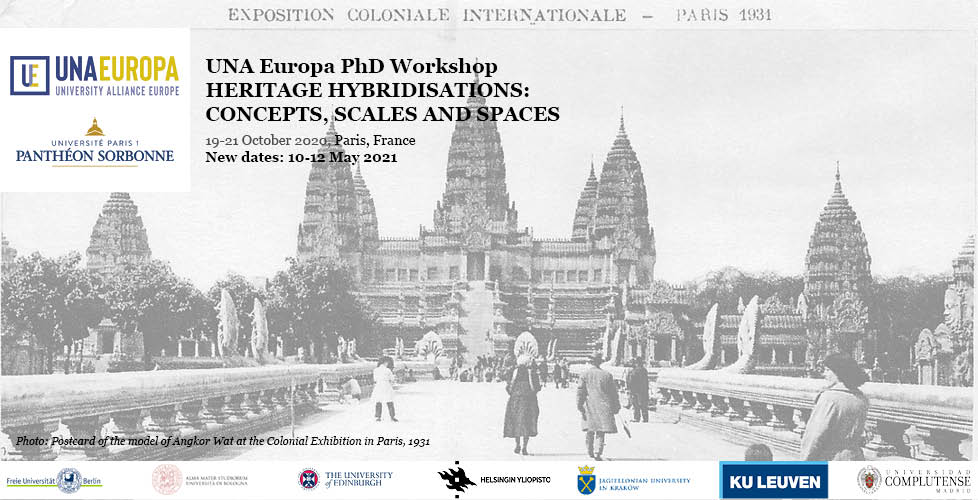

Theme and RationaleTraditional conceptions of heritage are often associated with a single cultural period (e.g. the Baroque period) or a defined political or cultural entity (e.g. a national monument). But, at the same time, heritage is also the result of accumulated layers of different temporalities and socio-cultural interventions. In this sense “the concept of cultural heritage itself is historically constructed as a hybrid social product” (Hernandez I Marti 2006, 91). Hybridisation enables us to focus on the interconnection of different domains, temporalities and actors at different levels, overcoming and rejecting hierarchies, and grand narratives (Lyotard 1979). The emergence of the “trans”, the plural and the augmented enables us to frame critical perspectives on heritage constructs (Gwiazdzinksi 2016). Originating from the language of biology, the term “hybridisation” refers to the natural or artificial crossbreeding of two different species, breeds or varieties of plants or animals (see e.g. Schwenk, Brede and Streit 2008). It has been used figuratively by researchers in different fields to express the state of something that has a disparate and surprising composition. In the social sciences literature, for example, “hybridisation” is commonly associated with a reflection on modern or postmodern conditions and expressions (Hernandez I Marti 2006; Boutinet 2016; Gwiazdzinksi 2016) and is used to shed light on new forms of culture and identity (Canclini 1990; Pieterse 1994; Rubdy and Alsagoff 2013; Appadurai 2014). In the field of geography, Claval (2016) referred to the term to describe epistemic changes in science of territory since the 1990s; and Vanier (2016) used the term in the sense of an innovative process that helps individuals overcome traditional rules and critical situations. Hybridization becomes part of a territory’s characteristic, contributing to its own particular identity. Heritage hybridisation can be understood in this sense. From an ethical perspective, it can be associated with the emergent conditions of new heritage governance regimes (Paquette 2012), such as the opening up of the expertise process to local know-how. Moreover, heritage’s specific position at the intersection of an imaginary past and a reinvented present generates the conditions required for hybridisation. Heritage hybridisation is thus linked to social and cultural practices, knowledge exchanges and the functions, values and meanings that heritage conveys. Heritage hybridisation has often been associated with postcolonial perspectives and the works of postcolonialist theorists, such as Saïd (2004) and Bhabha (1997). Further, hybridity has been perceived by several schools of thought as one of the main weapons against colonialism (Andrade 2013). Classical Heritage process preserves the past by preserving its material traces: valorising rather than criticizing. Its ideal is the sharing of common values, contributing to community continuity and posterity. Heritage status confirms a judgement of value. More recently, sustained by classic frames (monuments, museums or archives) but also by contemporary media, it plays a role of unprecedented importance in the public sphere, fuelled by new memorial obligations. Communities or nation-states are asked to deal with multiple demands for recognition in relation to the representation of minorities, traumas, or difficult pasts. How does hybrid heritage result from these negotiations for institutional and political recognition on a specific territory or in a transnational context? Who are the actors and what are their processes of negotiation? Cultural heritage has always been caught in a tension between the display of a positive collective self-presentation, and the embarrassment of collective failure. Heritage may represent images of shame as well as glory, provoking various emotions, and exposing them to a contestation of values. David Lowenthal (2015) has described heritage conscience as the representation of a past appropriated by a community for exclusively instrumental ends, dedicated to promoting local or identity-driven stories that are more devoted to the glorification of mythicized than “authenticity” or “truth”. Historians or curators have often been instrumental in this (re)invention of tradition or “authorized discourse” (Smith, 2006). However, as Jay Winter argues, “the ways that sites of memory and the public commemorations surrounding them have the potential for dominated groups to contest their subordinate status in public”. Can heritage hybridisation be also understood as a means of, and a challenge to, social appropriation? Over the past two decades, the recognition and rise of material culture and consumption studies, the anthropology of the material world and the material history of art have focused on the ways in which objects mediate social relationships. Aleida Assmann (2010) uses a classical division between two separate functions of cultural heritage: “the presentation of a narrow selection of sacred texts, artistic masterpieces, or historic key events in a timeless framework; and the storing of documents and artefacts of the past”. According to her, there is no strict separation between passive cultural memory and the construction/curation of memorial places or spaces. What are the processes of (hybrid) heritage production as a “contact zone” between high and popular culture? In Europe and elsewhere, the ownership of heritage is increasingly subject to publicly debated restitution claims. The passage of property between different owners and through different types of collections offers fertile ground for analysis, in terms of both the different conception of private and public property in different countries, and also in terms of antagonistic values or representations of identity. Judicial cases concerning contested objects can relate to contexts of colonial appropriation and post-colonial claims, to processes of secularisation, to situations of war and plunder, to archaeological findings in territories where national frontiers have changed or are disputed. How do international debates, diplomacy and NGO movements tackle heritage rescaling and hybridisation? Western conceptions of heritage have been globally dominant for two centuries. Material-based authenticity has dominated approaches to conservation, restoration and display. However, those approaches are increasingly challenged by a “Southern” turn. The circulation of norms, doctrines, practices and savoirs-faire, due to mobility, the work of NGOs such as UNESCO, or the creation of international conservation and restoration bodies (such as the ICC – International Conservation Committee in Angkor bringing together international experts and many governments) tends to blur existing doctrines. Contemporary conservation and restoration projects are the result of intercultural negotiated approaches, tending to relativize the supremacy of material authenticity, and encouraging, for example in architecture, monumental restorations or anastyloses about which Western experts are often squeamish. What new hybridisations are emerging within global conceptions of heritage conservation and display? |